Douglas drew a lot of inspiration from third world struggles and used art as the primary method of propaganda and outreach. His graphics served to promote the Party's ideologies, which were inspired by the rhetoric of revolutionary figures such as Malcolm X and Che Guevara. His images were often very graphic, meant to promote and empower black resistance with the hope of starting a revolution to end institutionalized mistreatment of African Americans.

Douglas worked at the black community-oriented San Francisco Sun Reporter newspaper for over 30 years after The Black Panther newspaper was no longer published. He continued to create activist artwork, and his artwork stayed relevant, according to Greg Morozumi, artistic director of EastSide Arts Alliance in Oakland, California: "Rather than reinforcing the cultural dead end of 'post-modern' nostalgia, the inspiration of his art raises the possibility of rebellion and the creation of new revolutionary culture."

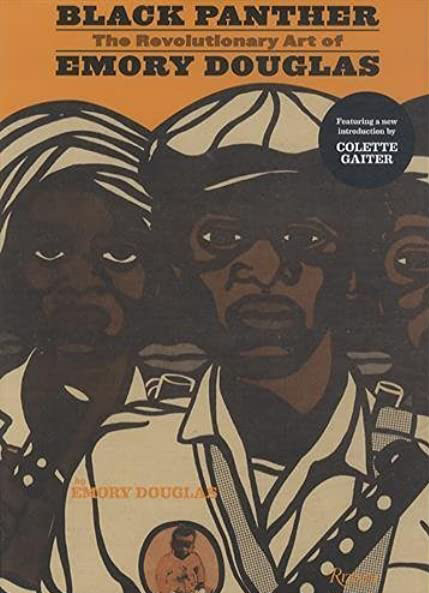

In 2006, artist and curator Sam Durant edited a comprehensive monograph on the work of Douglas, Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas, with contributors including Danny Glover, Kathleen Cleaver, St. Clair Bourne, Colette Gaiter (associate professor at the University of Delaware), Greg Morozumi, and Sonia Sanchez.

After the monograph's publication, Douglas had retrospective exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2007–08) and the New Museum in New York. Since the re-introduction of his early work to new audiences, he continues to make new work, exhibit and interact with audiences in formal and informal settings all over the world. His international exhibitions and visits include Urbis, Manchester(2008); Auckland, a collaboration with Richard Bell in Brisbane (2011); Chiapas; and Lisbon (2011).

Douglas was the most prolific and persistent graphic agitator in the American Black Power movements. Douglas profoundly understood the power of images in communicating ideas ... Inexpensive printing technologies—including photostats and press-type, textures and patterns—made publishing a two-color heavily illustrated, weekly tabloid newspaper possible. Graphics production values associated with seductive advertising and waste in a decadent society became weapons of the revolution. Technically, Douglas collaged and re-collaged drawings and photographs, performing graphics tricks with little budget and even less time. His distinctive illustration style featured thick black outlines (easier to trap) and resourceful tint and texture combinations. Conceptually, Douglas's images served two purposes: first, illustrating conditions that made revolution seem necessary; and second, constructing a visual mythology of power for people who felt powerless and victimized. Most popular media represents middle to upper-class people as "normal." Douglas was the Norman Rockwell of the ghetto, concentrating on the poor and oppressed. Departing from the WPA/social realist style of portraying poor people, which can be perceived as voyeuristic and patronizing, Douglas's energetic drawings showed respect and affection. He maintained poor people's dignity while graphically illustrating harsh situations.

Colette Gaiter

Douglas is now retired but does freelance design work discussing topics such as Black on Black Crime and the prison industrial complex. His more current works features children. He feels he must continue to educate through his work.